Medical Disclaimer: This is educational content only, not medical advice. Consult a licensed healthcare provider for diagnosis/treatment. Information based on sources like WHO/CDC guidelines (last reviewed: 2026-02-13).

Congenital Heart Disease Complete Guide Causes Types Diagnosis and Treatment

Frequently Asked Questions

Congenital heart disease (CHD) refers to structural or functional abnormalities of the heart or great vessels that are present at birth due to abnormal cardiac development during embryogenesis.

Congenital heart disease occurs in approximately 8–10 per 1,000 live births, making it the most common congenital anomaly worldwide.

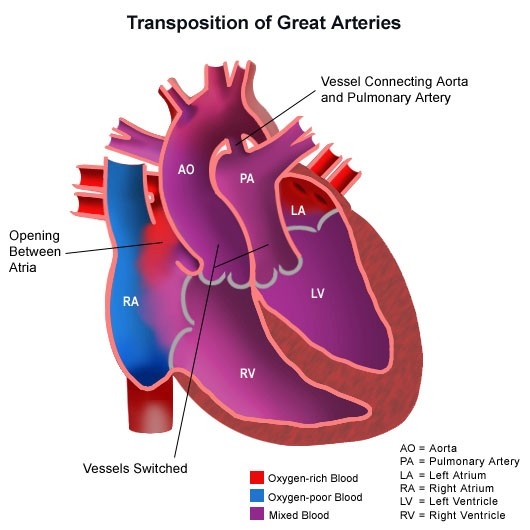

CHD is broadly classified into acyanotic defects (such as ASD, VSD, PDA), cyanotic defects (such as Tetralogy of Fallot, Transposition of Great Arteries), obstructive lesions (coarctation of aorta, aortic stenosis), and complex congenital heart diseases.

Causes include genetic factors, chromosomal abnormalities, maternal diabetes, maternal infections like rubella, teratogenic drug exposure, alcohol use, and multifactorial environmental influences.

Common symptoms include cyanosis, rapid breathing, poor feeding, failure to thrive, excessive sweating, lethargy, and signs of heart failure or shock.

Duct-dependent CHD refers to defects where systemic or pulmonary circulation depends on a patent ductus arteriosus for survival, requiring prostaglandin E1 infusion to maintain ductal patency.

Diagnosis is made using clinical examination, pulse oximetry screening, echocardiography, ECG, chest X-ray, and advanced imaging such as cardiac MRI or cardiac catheterization when required.

Yes, many congenital heart defects can be detected prenatally using fetal echocardiography, usually performed during the second trimester.

Eisenmenger syndrome is a late complication of uncorrected left-to-right shunt lesions where long-standing pulmonary hypertension leads to reversal of the shunt and development of cyanosis.

Treatment depends on the defect and may include medical management, catheter-based interventions, or surgical correction, along with long-term follow-up and supportive care.

No, small defects may close spontaneously or remain asymptomatic, while moderate to severe defects usually require interventional or surgical correction.

Common medications include prostaglandin E1, diuretics, ACE inhibitors, beta blockers, antiarrhythmics, and anticoagulants depending on the condition and complications.

Long-term complications may include heart failure, arrhythmias, pulmonary hypertension, infective endocarditis, exercise intolerance, and need for re-intervention.

Yes, most children with CHD now survive into adulthood due to advances in medical and surgical care, but many require lifelong follow-up in adult congenital heart disease clinics.

Endocarditis prophylaxis is recommended only for high-risk conditions such as unrepaired cyanotic CHD, prosthetic valves, or previous infective endocarditis.

Many women with CHD can have successful pregnancies, but pregnancy requires careful risk assessment and management by a multidisciplinary cardiac and obstetric team.

Prevention includes good antenatal care, control of maternal illnesses, avoidance of teratogenic drugs, vaccination against rubella, genetic counseling, and early screening.

Prognosis varies widely depending on the type and severity of the defect; simple lesions often have excellent outcomes, while complex CHD requires lifelong care.