Medical Disclaimer: This is educational content only, not medical advice. Consult a licensed healthcare provider for diagnosis/treatment. Information based on sources like WHO/CDC guidelines (last reviewed: 2026-02-13).

Aortic Stenosis Complete Clinical Guide Causes Symptoms Diagnosis Treatment

Frequently Asked Questions

Aortic stenosis is a valvular heart disease characterized by narrowing of the aortic valve opening, leading to obstruction of left ventricular outflow, increased pressure load on the left ventricle, and reduced cardiac output.

The most common causes are degenerative calcific aortic stenosis in elderly patients, bicuspid aortic valve in younger individuals, and rheumatic heart disease in endemic regions.

The classic triad includes exertional angina, syncope or presyncope, and dyspnea due to heart failure. Symptoms usually indicate advanced disease and poor prognosis without intervention.

Angina occurs due to increased myocardial oxygen demand from left ventricular hypertrophy and reduced coronary perfusion reserve caused by elevated intraventricular pressures.

Findings include a harsh ejection systolic murmur at the right upper sternal border radiating to the carotids, pulsus parvus et tardus, narrow pulse pressure, soft or absent A2, and a sustained heaving apex beat.

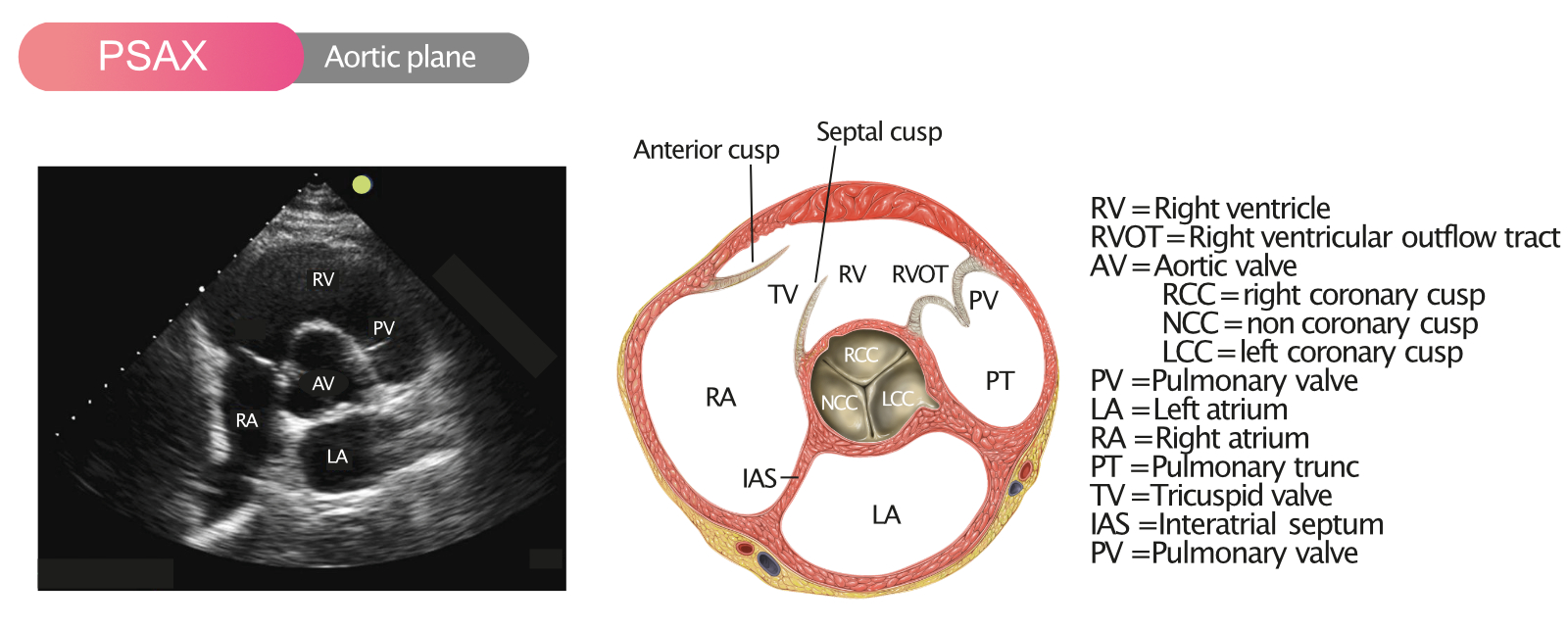

Severity is assessed using peak aortic jet velocity, mean transvalvular gradient, and aortic valve area calculated by the continuity equation.

Severe aortic stenosis is defined by aortic valve area ≤ 1.0 cm², peak velocity ≥ 4.0 m/s, or mean gradient ≥ 40 mmHg.

It is a subtype of severe aortic stenosis where transvalvular gradients are low due to reduced stroke volume, often seen with reduced ejection fraction or paradoxically with preserved ejection fraction.

Low-dose dobutamine stress echocardiography is used to assess contractile reserve and changes in valve area to distinguish true severe from pseudo-severe aortic stenosis.

No, medical therapy does not halt disease progression or improve survival in severe aortic stenosis. Definitive treatment requires aortic valve replacement.

It is indicated in all patients with severe aortic stenosis who develop symptoms or left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and in selected high-risk asymptomatic patients.

The two main types are surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) and transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).

Elderly patients, those with high or prohibitive surgical risk, and selected intermediate-risk patients after heart team evaluation are preferred candidates for TAVR.

Balloon aortic valvuloplasty is used as a temporary bridge to definitive valve replacement or as palliative therapy in patients who are not candidates for SAVR or TAVR.

Complications include heart failure, atrial fibrillation, ventricular arrhythmias, sudden cardiac death, pulmonary hypertension, and gastrointestinal bleeding due to Heyde syndrome.

Heyde syndrome is the association of severe aortic stenosis with gastrointestinal angiodysplasia and acquired von Willebrand factor deficiency, leading to recurrent GI bleeding.

Patients with aortic stenosis rely heavily on atrial contraction for left ventricular filling, and loss of atrial kick can rapidly precipitate heart failure.

The prognosis is poor, with a median survival of approximately 2 to 3 years once symptoms develop.

They require close clinical monitoring, periodic echocardiography, and exercise testing in selected cases to detect early symptom development or disease progression.

There is no proven therapy to prevent degenerative aortic stenosis, but controlling cardiovascular risk factors and early detection in bicuspid valve disease may help delay complications.